This project uses Python to demonstrate the steps for preparing a dataset with multiple variables and data types, and then selecting the appropriate features that contribute to a specific outcome; in this case, hospital length of stay.

The dataset contains about 32,000 records with data consisting of patient demographics, diagnoses, medical history, and vital signs. This data is fictitious, but represents true clinical outcomes and values.

Table of contents

- 00. Project Overview

- 01. Concept Overview

- 02. Data Overview & Preparation

- 03. Applying RFECV for Feature Selection

- 04. Analyzing The Results

- 05. Discussion

Project Overview

Context

Preparing, or “cleaning”, a dataset is an important first step before attempting to use the data for analysis or with a Machine Learning model. Dealing with extreme or missing values and correcting / converting data types are common steps in this process. Datasets often have variables that are unnecessary for making predictions on the outcome under investigation and steps should therefore be completed for removing them.

This dataset came to me as part of a coding test for a position I chose not to pursue. The test requirement was to prepare the dataset for use with predictive models and specifically, for predicting hospital length of stay as the outcome variable. There are multiple clinical and non-clinical input variables included. While I did well enough at the time with the task, looking back on it, I realized I could have coded it more efficiently, so when I began building this portfolio, I decided to revisit it as a project for inclusion.

Actions

This project focuses on completing the steps for dealing with extreme values (i.e., outliers), missing values, converting categorical values, and performing feature scaling before using a technique called Recursive Feature Elimination with Cross-Validation (RFECV) to perform Feature Selection. For the RFECV process, I use the RFECV module from the Sci-Kit Learn library. Full details of this module and the concept behind its use are in the dedicated section below. Coding samples are included.

My first step with any project is to import the required packages that I’ll use. I then import the dataset, generally as a Comma-Separated Values (CSV) file, into a dataframe using the Pandas library.

Note: while the data preparation steps typically occur after the dataframe is constructed, if I’m the person retrieving the raw data (i.e., writing the SQL), I’ll often do some of the preparation in SQL first. Examples include compressing the data to the proper cardinality, grouping the data into appropriate groups, or creating Boolean (1/0) columns from the raw data values. I may have to repeat these steps after creating the dataframe in Python, but I often save time by doing as much of this in SQL first.

I next perform the following steps:

Data Preparation

- Check the shape of the dataframe

- Check for duplicate rows

- Drop the duplicate rows

- Recheck the shape to confirm the previous drop

- Check for missing values

- Determine the percentage of missing values for each variable

- Drop or impute missing values

- Review the data types of the variables

- Perform data type conversions / convert categorical variables to numeric

- Check for extreme (outlier) values

- Perform feature scaling, if indicated

- Shuffle the data, if indicated

Feature Selection with RFECV

- Create variables for inputs and outputs

- Instantiate the regressor and selector objects

- Fit the variables

- Identify the optimal number of features

- Identify the chosen features

- Plot the results for the optimal number

- Sort and rank the chosen features by an appropriate statistic

Note: the above steps are outlined at a high level and describe how I generally prepare data and perform feature selection, but are not meant to imply any absolutes. It is important to recognize that others may have their own, albeit similar, process. Some of the above steps may also occur in different sequences depending on the project needs.

Results & Discussion

The initial dataframe presents with 32,000 rows and 221 columns (features). There are 8790 duplicate rows and dropping these results in 23,210 remaining rows. Checking for missing values results in input variables missing between 5 - 98% of values. Because of this widespread variability, I chose not to impute any missing values, even for input variables with low percentages. Because this is clinical data, if this were being used for a machine learning model, it is likely more appropriate to use factual data, as opposed to imputed, since no two patients are 100% alike. Therefore, I chose to drop any features that contained missing values.

This action reduced the number of columns from 221 to 49! The upside to such an action is the dimensionality reduction that occurs, which likely results in less overall complexity, less required storage space, and improved computational time. The downside to this includes potentially losing important data, which can affect model training later. Still, in reviewing the columns that remained after dropping, they all seemed to be clinically relevant, and I felt satisfied with the decision, especially knowing that this can always be revisited using a different approach.

With the remaining columns, I dropped an unnecessary column for encounter ID as this column had no value other than to create noise and take up feature space. From there, I checked for extreme values, or outliers. I used a Boxplot approach for this where I created a for loop that passed over all of the remaining continuous numeric variables and identified the outliers based on threshold borders set around the 25% and 75% quartiles, or the interquartile range (IQR), from the respective column values. The decision to keep or remove outliers from the data always depends on the data and what you intend to do with it. From the outliers assessment, I determined there were relatively few. I chose to include the outliers because, in reality, these values WOULD contribute to a patient’s length of stay, and so, are clinically appropriate.

Next, I shuffled the data and converted variables that presented as numeric, but were actually categorical. I then performed One Hot Encoding on the categorical variables to convert these to Boolean (1/0) values. I used the OneHotEncoder module from Sci-Kit Learn for this step.

One Hot Encoding can be thought of as a way to represent categorical variables as binary vectors, in other words, a set of new columns for each categorical value with either a 1 or a 0 saying whether that value is true or not for that observation. These new columns would go into our model as input variables, and the original column is discarded.

I dropped one of the new columns using the parameter drop = “first” to avoid the dummy variable trap, where the newly created encoded columns perfectly predict each other and this runs the risk of breaking the assumption that there is no multicollinearity. This is a requirement, or at least an important consideration, for some models, Linear Regression being one of them. Multicollinearity occurs when two or more input variables are highly correlated with each other, and while it won’t necessarily affect the predictive accuracy of models used with this dataset, it can make it difficult to trust the statistics around how well the model performs.

From performing One Hot Encoding, the number of input variables increased to 60.

Next, I scaled the remaining numeric data to a Normalized scale, so that these features would not be inappropriately weighted higher than the other features. I used the MinMaxScaler module from Sci-Kit Learn to do this. I created a new normalized dataframe after the scaling action.

Finally, with the data in a prepared state in a new dataframe, I performed the steps for Feature Selection listed above. As these steps are more technical, I describe those more in the “Applying RFECV for Feature Selection” section.

Since the output variable (Length of Stay) is a continuous numeric variable and because I chose to keep the outliers in the dataset, I chose a Random Forest Regressor for use with the RFECV selector object. Random Forests, by nature, are less sensitive to outliers, so it made sense to use this for the Regressor object used by the RFECV selector. The selector identified 13 inputs as the optimal number of features and I ranked these by their mean cross-validation test score. The input variable, “Chronic Condition Count’, had the highest score and a rank of 1 with “Age” coming in 13th with the lowest score.

Concept Overview

Data Preparation & Feature Selection

There are likely many definitions and variations on what it means to prepare data for analysis and machine learning depending on the source. I put my own spin on a definition that I liked from Databricks where they define Data Preparation (also referred to as “data preprocessing”) as the process of transforming raw data, so that data analysts and data scientists can run it through machine learning algorithms to uncover insights or make predictions. Another benefit to having properly prepared, or “cleaned”, data is that machine learning models will perform better than with messy, or unprepared data. Messy data surely means many things for different audiences, but one interpretation is that messy data includes missing values, unscaled data, unstructured data, variables with incorrect data types, and whitespace. This is not an exhaustive list and is simply meant to provide some high-level reasoning for why data needs to be processed before a machine learning algorithm, let alone a human, can interpret or use it.

A basic and easy to understand definition for Feature Selection comes from Simplilearn where they define it as “the method of reducing the input variable to your model by using only relevant data and getting rid of noise in data. It is the process of automatically choosing relevant features for your machine learning model based on the type of problem you are trying to solve.” Feature Selection is similar to Data Preparation in that there is the need for optimal model performance and interpretability, both of which occur when the “noisy” inputs are removed.

Data Overview and Preparation

The data preparation steps are detailed in the Jupyter Notebook for this project here.

The initial dataframe presents with 32,000 rows and 221 columns (features) of various clinical data. Through a series of data preparation steps, I arrived at 48 remaining feature columns. Performing One Hot Encoding on the categorical variables increased the number of features to 60. I then scaled all features to a normalized scale, given that most already consisted of 1/0 values.

Applying RFECV for Feature Selection

Feature Selection is the process used to select the input variables that are most important to your Machine Learning task. It can be a very important addition or at least, consideration, in certain scenarios. The potential benefits of Feature Selection are:

- Improved Model Accuracy - eliminating noise can help true relationships stand out

- Lower Computational Cost - our model becomes faster to train, and faster to make predictions

- Explanation - understanding & explaining outputs for stakeholder & customers becomes much easier

One method for performing Feature Selection is Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE), which is an approach that starts with all input variables, and then iteratively removes those with the weakest relationships with the output variable.

I applied a variation of RFE called Recursive Feature Elimination with Cross Validation (RFECV) which splits the data into many “chunks” (this is the Cross-Validation piece), and iteratively trains and validates a predictive model (called the “estimator”) on each “chunk” separately. The estimator selects the best subset of features by removing 0 to N features, where N is the number of features, using recursive feature elimination, then selecting the best subset based on the mean cross-validation score of the model. Different models (estimators) can be used with this approach, depending on the types of variables and outputs.

For this project, I used a Random Forest Regressor as the estimator, since the output variable is a continuous numeric variable, and because I chose to retain the outliers. Random Forests are generally less sensitive to outliers which made this a good choice for use as the estimator with the RFECV selector.

Analyzing the Results

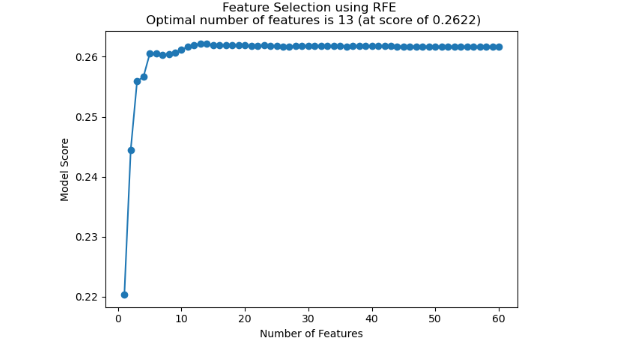

The RFECV selector chose 13 optimal features based on the mean cross-validation test score. In the plot below, there is no further improvement in the mean score after the feature count of 13, so this becomes the optimal number of features.

Ranking the features by mean cross-validation test score yielded the below features ranked by their score:

- Chronic Condition Count

- Is Chronic Condition Acute Myocardial Infarction

- Is Chronic Condition Asthma

- Is Chronic Condition Anemia

- Days Since Last Inpatient Encounter

- Is Admit Source Medical Professional

- Is Chronic Condition Ischemic Heart Disease

- Is Chronic Condition Heart Failure

- Is Admit Source Emergency MD

- Procedures Count

- Hospital Admit Count Past 12 Months

- Hospital Admit Count Past 3 Months

- Age of Patient

Discussion

The features selected from the RFECV process logically contribute to a patient’s length of stay, so while the selections are not necessarily surprising, it would be interesting to see what the outcome might be if different data preparation steps are followed in the future, such as dropping outliers or imputing missing values, if clinically appropriate. This might change the model type then used as the RFECV estimator, likely resulting in different feature selections.

With the approach used for the project, the next steps would be to construct a dataframe with the selected features and use it with different regression machine learning models like multiple linear regression, random forest regression, or even other more advanced models, like Support Vector Regression. I will tackle this in a future project, so stay tuned!

Headline photo courtesy of No Revisions via https://unsplash.com/photos/cpIgNaazQ6w.